A complex distributed computing problem application developers may encounter is controlling access to a resource or entity in a multi-user, concurrent environment. How can we guard against an arbitrary number of concurrent processes from potentially mutating or even having any access to an entity simultaneously? One possible solution is to rely on database management systems which provide concurrency safeguards via ACID transactions and row-level locking.

In this article you'll learn how I combined various technologies like Postgres, SQL, and Node.js and created an application which implements a Distributed Lock State Machine.

In understanding the approaches taken here, you'll learn how commitment control, isolation levels, and ACID transaction guarantees can be applied to implement a distributed lock state machine. In this context, "distributed" means multiple concurrent processes. The "lock" is the safety mechanism that safeguards against concurrent processes from gaining access to shared resources or entities simultaneously. Finally, "state machine" means those concurrent processes will have the ability to identify a resource or entity in a specific state (e.g. new, in-progress), perform some work or processing on them, and transition them to a final, settled state (e.g. complete, error).

At the end, I'll provide additional examples of the implementation that can be applied to achieve robust data aggregation and replication without requiring changes to your existing applications.

An example use case

Recently, I've been working with applications that construct Google Sheets with user-driven data. The spreadsheet link is given to the user and the users can update the contents of the worksheet followed by clicking a hyperlink to effectively "send back" the data to the server for processing.

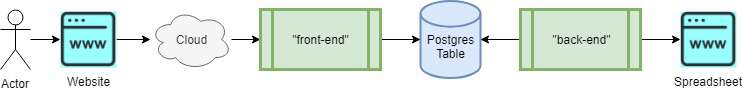

Here is the gist of the setup:

- A "front-end" application, which is responsible for receiving and recording requests to either

createorupdatea spreadsheet - A "back-end" application that uses SQL and commitment control to locate, process, and finalize the outcome of the requests for future logging

Each application is independently scalable and runs in a distributed cloud computing environment.

The two components communicate via a "hand-off plane", which is a SQL table. Additionally, a simple, event-driven notification system is employed via two SQL statements issued against the Postgres server.

Here is a high-level overview of how the components interact:

Creating the hand-off plane

When a user requests a spreadsheet to be created or updated, a REST call is made to the "front-end" application, which is ultimately a Node.js Express server. The Express server then (in addition to validation, JWT authentication, etc.) creates an entry in an SQL table. The newly created row contains the sufficient information to be acted upon later.

This SQL table has a couple key columns that are important in understanding the state machine implementation.

The first state variable is request_status. This is simply a TEXT column in a Postgres table that could be any of the following four values:

newin-progresscompleteerror

All rows written to the table would have a default request_status of new. As the requests are chosen (more to come), the row is updated to in-progress. Upon completion of the request, the row would then settle to the value of either complete or error, depending on the outcome.

The second state variable is process_id. This is also a TEXT column and would represent the "identity" of the process responsible for implementing the request. This value ultimately is a UUID, generated at run-time for each request being processed (more to come on that as well).

There are additional columns such as the URL to the spreadsheet, the identity of spreadsheet, the type of request (create/update), and various other relevant pieces of information. The two state variables described previously are ubiquitous for any process that follows this pattern.

CREATE SEQUENCE spreadsheets.request_queue_id_seq; CREATE TABLE spreadsheets.request_queue ( request_queue_id BIGINT NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT NEXTVAL('spreadsheets.request_queue_id_seq'), request_status TEXT NOT NULL DEFAULT 'new', request_type TEXT NOT NULL DEFAULT 'create', process_id TEXT, spreadsheet_id TEXT NOT NULL, CONSTRAINT CHECK ( request_status IN ( 'complete', 'error', 'in-progress', 'new' ) ), CONSTRAINT CHECK ( request_type IN ( 'create', 'update' ) ) ); CREATE UNIQUE INDEX request_queue_01 ON spreadsheets.request_queue ( spreadsheet_id, request_type ) WHERE ( request_type = 'create' );

The constraints above provide some basic data integrity at the database layer. Additionally, the sparse unique index ensures that only one create request can exist for any one spreadsheet.

Communication channel

The "front-end" application is be able to receive any number of concurrent requests to either create or update a spreadsheet. For each such request, it then executes an INSERT statement to create a row in the SQL table described above, where the request (by default) is in new status.

INSERT INTO spreadsheets.request_queue ( request_type, spreadsheet_id ) VALUES ( 'create', -- could be 'update' also $1 -- the identity of the google spreadsheet );

In addition, the "front-end" executes a NOTIFY statement to "awaken" the "back-end" application, causing it to start searching for work.

NOTIFY spreadsheets_request_queue;

The "back-end" application is idle throughout the day until a user requests a spreadsheet to be created or updated. When this occurs, a row is written to the SQL table. The "back-end" application is made aware of the new row by having executed a LISTEN statement on the same topic as used by the NOTIFY statement.

This is a simplistic mechanism to implement an asynchronous communication channel between the "front-end" and "back-end" applications. The channel name can be a string of your choosing, with some limitations regarding white space and special characters. No additional setup is needed to create a channel.

It is important to note that only currently connected clients, which are already listening for a message to appear on the topic, will receive that notification. At first blush, you may think that some information is lost if the "back-end" is offline. As you'll come to find out this simplistic, asynchronous, lossy communication channel is perfectly suited for this event-driven design.

Priming the pump

The "back-end" application is designed to run independently of the "front-end" application. It can be offline indefinitely. This means that even if the requests are not being processed because the "back-end" is not running, requests to be processed are still being captured by the "front-end" application. While it will appear that the system is not responsive during the outage, no requests will be lost.

As and when the "back-end" application starts, one of the first things the "back-end" application does is execute the LISTEN statement and create an event listener. Using the pg module, this is easily done with the on method of the client, which is consistently connected to the Postgres database where the SQL table lives.

const { Client } = require('pg'); const client = new Client(); // setup event listener client.on('notification', async () => { ... }); // begin listening for notifications on the communication channel client.query('LISTEN spreadsheets_request_queue');

From that point on, the "back-end" application will receive any new notifications created by way of the NOTIFY statement executed by the "front-end" application. But what if the "back-end" application has been offline for some time, you ask?

In addition to executing the LISTEN statement to receive any new notifications, the "back-end" application effectively performs a self-notification by executing the NOTIFY statement itself. This causes the "back-end" to believe that some work is needing to be done and it starts searching for work immediately.

// prime the pump client.query('NOTIFY spreadsheets_request_queue');

Commitment control

To ensure database integrity, the "back-end" application uses commitment control. This allows the application to update rows without immediately making the changes permanent and also locks the rows to the application process.

To implement commitment control, the "back-end" application executes the BEGIN statement and uses COMMIT and ROLLBACK as needed, depending on the outcome of various actions.

BEGIN; -- start commitment control COMMIT; -- make changes permanent ROLLBACK; -- undo any pending changes

Using commitment control also means that if the "back-end" application dies suddenly for any reason (server outage, unexpected run time error, out of memory condition, etc.), uncommitted changes will also be automatically rolled-back by the database manager. This assures there will never be a row caught in a zombie-like state where it is always in-progress. Any row which was once new will always settle to complete or error, depending on the outcome. If any unexpected error occurs, any row which was temporarily transitioned to in-progress will assuredly be reverted to its original new state.

This does mean the application must be willing and able to tolerate the possibility that a spreadsheet was partially created or updated. This is not an inherent flaw in this distributed lock state machine; it is just a consequence that googleapis calls and spreadsheet interactions are not also under commitment control. In later sections, you'll learn how, when combined with your existing database tables, the distributed lock state machine implementation also cleanly handles and corrects partial transactions.

Searching for work

When the "back-end" application is awakened by a notification that some new request is ready to be processed, it first generates a process identifier that is unique against all other parallel processes. This can be achieved in a number of ways.

A simple, distributed approach is to create a UUID, which can give you a theoretically globally unique value in a distributed computing environment. In this example, I used the popular npm package uuid and the specific v4 implementation.

const uuid = require('uuid/v4'); const processId = uuid();

Note There is a caveat to this approach. It is entirely possible, although statistically impossible that two, duplicated UUID values can ever be created. If this is a concern, another approach to obtain a truly unique identifier is through a sequence object in the database itself. However, that has the drawback of additional database calls, entities, and permissions.

Once the process identifier is generated, the "back-end" application executes a searched UPDATE statement. In this searched update, the "back-end" application is looking for the first request in new status (which it has not already seen before—more to come).

Since the table also has a system-generated, ever-increasing unique identifier, the order of the rows is easily controlled. By ordering on the request identifier, the application processes the requests in FIFO order.

UPDATE spreadsheets.request_queue SET process_id = $1, -- that UUID request_status = 'in-progress' WHERE (request_queue_id) = ( SELECT request_queue_id FROM spreadsheets.request_queue WHERE ( request_status = 'new' AND request_queue_id > $2 -- see note below ) ORDER BY request_queue_id FETCH FIRST ROW ONLY FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED ) RETURNING request_queue_id, request_type, spreadsheet_id;

This statement has two critically important concepts that need to be understood.

First, the clauses:

FETCH FIRST ROW ONLY— return only the first row that meets the criteriaFOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED— tell the database manager that the row will be updated and skip any rows which are currently locked to any other process

Next, the "line-in-the-sand":

WHERE request_queue_id > $2— skip any rows where the unique identifier is less than the value provided

At application start-up the "line-in-the-sand" is the value 0. The table is setup such that the system-generated identity values begin at the value 1 and increase as each row is written to the table. This will become more clear next.

Recall that commitment control is in effect, so this row that is found and updated is only temporarily updated (not yet permanent) and it is locked to the process which updated the row. This ensures that no other process can update the row until the changes are either committed or the transaction is rolled-back.

Validation and grouping requests

The searched-update statement above will blindly update any row that meets the criteria. This means that the request_type could be either create or update. Depending on the outcome, the "back-end" application performs additional validations and grouping.

Handling create requests

If the type of request is to create, the "back-end" application can proceed with creating the spreadsheet. However, if the type of request is to update then two additional actions are taken.

Handling update requests

To be able to update a spreadsheet, the previous create request must already be completed. This is verified using the following SELECT statement:

SELECT true FROM spreadsheets.request_queue WHERE ( spreadsheet_id = $1 -- spreadsheet discovered in UPDATE AND request_type = 'create' AND request_status NOT IN ('complete', 'error') ) FOR UPDATE NOWAIT;

Examining the clause:

FOR UPDATE NOWAIT- do not wait if the row is locked

This statement will throw an exception (SQL State 55P03) if the create request for the same spreadsheet_id is locked to another process. This means that the create is still being worked on by a parallel process! When this occurs, the "back-end" application rolls-back the prior UPDATE and skips the row.

ROLLBACK;

The ROLLBACK statement resets the state of the previously updated row to new so it may be worked on again in the future. Additionally, the "line-in-the-sand" value alluded to earlier is updated to the identity of the row the "back-end" application already looked at.

The "back-end" application must still guard against updating a spreadsheet that is already being updated by another process. If two separate instances of the application were to update the same spreadsheet at the same time, the results would be unpredictable.

In the case of an update request, the "back-end" application prefers to "group-up" all outstanding update requests for the same spreadsheet. This is done to account for the scenario where a user might repeatedly click the update request and generate potentially dozens or more update requests. Ultimately, all outstanding requests to update will be considered a single request to update.

To accomplish this, another searched-update is performed:

UPDATE spreadsheets.request_queue SET processor_id = $1, -- the same UUID assigned to the process request_status = 'in-progress' WHERE ( request_queue_id IN ( SELECT request_queue_id FROM spreadsheets.request_queue WHERE ( spreadsheet_id = $2 -- spreadsheet discovered in UPDATE AND request_type = 'update' AND request_status NOT IN ('complete', 'error') ) FOR UPDATE NOWAIT ) );

In the above UPDATE statement, all the outstanding update requests for the same spreadsheet found to be worked on will be allocated to the same processor id (UUID).

As before, the FOR UPDATE NOWAIT clause will cause the statement to fail if there is a conflict. This will occur if there is a concurrent instance of the "back-end" application already updating the spreadsheet.

If this statement fails, then as before a ROLLBACK will occur and the "line-in-the-sand" will be set to the identity of the request found previously.

Progressing through the requests

If the transaction is not rolled-back, then the "back-end" application has successfully allocated either a single create request or one or many update requests of the same spreadsheet id. The spreadsheet is then created or updated accordingly.

Upon completion of the create or update, the request row(s) are updated one more time to indicate the outcome of the operation.

UPDATE spreadsheets.request_queue SET request_status = 'complete' -- or 'error', if there is one WHERE ( process_id = $1 -- the same UUID assigned to the process );

The above searched UPDATE statement will update all the request(s) that were previously locked to the process by the identity generated at run-time. This will either be the single create request or one or many update requests to the same spreadsheet.

At this point, the "back-end" application can safely commit its changes.

COMMIT;

The "back-end" application iterates through the data by beginning again with a search for the first outstanding new request but this time the search begins after the request_queue_id found previously.

This process continues until no more rows are returned by the search, or if all the candidate rows need to be skipped due to concurrent processes as described above.

Dealing with concurrency

What happens if there are rows skipped? How will the "back-end" application be assured everything gets processed if it is intentionally skipping requests?

To handle this, the "back-end" application makes the assumption that if any request to create or update is found and processed, then it is possible another concurrent processor was forced to skip a row that should have been processed.

Thus, the "back-end" application iterates until no more rows are returned by the search and no work is actually performed. After each complete turn of looking through the request table, the "line-in-the-sand" state variable will reset to its initial value of 0 and if any rows were locked in the prior iteration, all possible rows which are in new status will be again examined.

Only when the "back-end" application finds zero rows in new status will it enter an idle state. At which time, it will wait once more for the NOTIFY statement to be executed by the "front-end" application when a user makes a new request to either create or update a spreadsheet.

Detailed explanation example

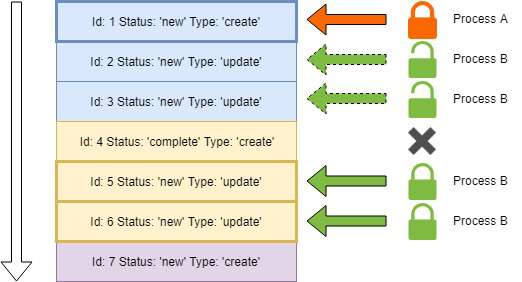

Let's now visualize with an example of how the flow works. Consider the following image:

The arrow on the left is the order in which rows will be found by way of the ORDER BY clause, specified in the searched-update.

Assume that each horizontal, colored box represents an entry in the request_queue table. Each color also represents a request corresponding to a single spreadsheet. For example, the first three boxes represent a create and two update requests to the same spreadsheet.

If Process A and Process B are two arbitrary instances of the "back-end" application running, then the lock icons you see depict what rows will be processed by the respective instances.

In the example, Process A is awakened by a NOTIFY statement from the "front-end". It locates the first row where the request_status is new. This is the first row in the table.

That row is updated to in-progress and is locked to Process A.

Similarly, Process B is awakened by a NOTIFY statement, or perhaps it just happens to come online after some requests are already present in the table. When it awakens, it too will find the first row where the request_status is new. Since Process A has already locked the first row, the first row is skipped and it finds the second row.

The second row in the table is an update request for the same spreadsheet that Process A is working on. When Process B gets the update request, it checks whether the create request for the same spreadsheet is complete.

In this example, that is not the case since Process A is still running. As a result, Process B receives a row-lock exception identified with SQL state 55P03. Thus, Process B performs a ROLLBACK statement and advances its "line-in-the-sand" to identity 2, the first row it found to work on. Process B then iterates and finds the next row, identity 3.

Again, in this example, Process A is still in the process of creating the spreadsheet, so again Process B must abort trying to update the spreadsheet since it receives a row-lock exception when trying to validate the create request is completed. The "line-in-the-sand" for Process B advances to identity 3.

On the next iteration for Process B, it skips identity 4 because it is already complete. It then discovers and locks identity 5 and determines it to be an update request. Process B successfully validates the create request is complete and also successfully identifies and locks all the related update requests for the same spreadsheet. All the outstanding update requests are allocated to Process B by performing the searched-update to update the status for all related spreadsheet identities.

Since both Process A and Process B found work, they assume they probably blocked another process from performing work they have found. So, both those processes will iterate through the remainder of the table by advancing with the "line-in-the-sand" concept until no more rows are found. Since they assume some rows were probably skipped, they start again from the beginning and either Process A or Process B will find the skipped rows and process them.

Additional applications

There are a number of additional applications of this technique. One such use-case is replication and aggregation.

In other settings, I have used this same approach to intercept changes to tables via SQL triggers, which would in much the same way record an event for later processing. You could attach a trigger to an SQL table and have that trigger INSERT the row into the queue-like table on your behalf.

In doing so, you've achieved a number of important and desirable capabilities and guarantees:

- 100% guaranteed delivery. Regardless of the interface, be it an API or an ad-hoc SQL query, any and all changes to the table(s) of interest will always be intercepted and recorded.

- Separation of concern. Applications should not necessarily understand that there is some behind-the-scenes aggregation or replication occurring. By recording the changes in the database layer, the application layer is not made aware of this and can perform their functions without those concerns. Additionally, by offloading the responsibility to the database layer, the application does not have an additional burden of notifying downstream systems of the changes.

- No phantom changes. Since the trigger runs in-line with the originating transaction, if that transaction fails and therefore is rolled-back, so too is the log of the change. Since rows that are not committed are also locked to the process which modifies them, the background processor will never read (because it cannot see) uncommitted changes.

- Transactional boundary. Using commitment control, you can read a row from the queue-like table, perform your aggregation or replication and if that fails you can

ROLLBACKand keep your intercepted changes in a pristine state. - History Log. The queue of transactions need not necessarily be purged. In doing so, your record of changes provides the knock-on benefit of providing a searchable history log.

One practical example is aggregating data from multiple disparate sources into a single source of truth.

In the past, I have used this technique to intercept changes to 17 different tables containing lots of different pieces of information regarding customer orders including addresses, names, phone numbers, ad-hoc warranty notes, items and item information, and so on.

Using the same technique described above, a queue-like table was developed and 17 SQL triggers were attached to the source tables, which in turn wrote to the table. The applications which were updating these various tables were never made aware of these triggers and were also not impacted by the replication process. Moreover, the applications that were updating those tables were quite old and monolithic in nature, so adding replication or message propagation logic to those legacy applications was neither feasible nor desirable. Writing an additional row in-line with a transaction is very lightweight so the original applications were not burdened by the change. The background process had the burden of understanding what to do with those changes.

The background process in this case read those entries from the history log and scraped all the relevant information about the customer order and created entries in another table which provided a massively powerful capability to search against bits of data about the order. The net result was a Google-like query engine, searching against two billion rows of textual data that gave the business the ability to find any order of interest in a sub-second. Prior to this new system, the business literally would spend hours and even days trying to find just one order so that warranty information could be located and appropriate customer interaction taken.

Upcoming article

In an upcoming article, I'll dive deep into how I built the Google Spreadsheets, exploring the googleapis npm module and devising solutions to adhere to rate limited quotas through request batching.